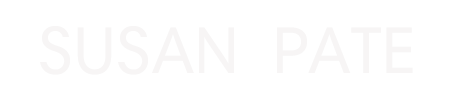

Students in the Bridge Golf Foundation program, based in Harlem, make their way to the golf course at the Bridge, a club in Bridgehampton that is owned by one of the foundation’s creators. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

The Power of Golf to Bring Change

At Compass, we're all about helping people find their place in this world. A growing golf centre in Harlem is doing exactly that! Helping underprivileged and mostly young minority men find their place in this world through the game of golf. As a progressive real estate brokerage, we aim to do the same.

By PAUL ROGERS | NEW YORK TIMES

Two years ago, Juan Cortorreal had never held a golf club. And now here he was, a freshman from the Eagle Academy for Young Men of Harlem, competing against the top player from the Bronx High School of Science, one of the city’s best teams.

As his team’s No. 1 man, Juan had to tee off in the first group, in front of a crowd, at the Mosholu Golf Course in the Bronx, toward the end of the school year last May. Everyone fell hushed as he settled into his stance. With a patient backswing and whiplike follow-through, he sent his ball flying up the tree-lined fairway. He outdrove his opponent, a far more seasoned player, but proceeded to lose the hole and, eventually, the match, just as he had every other match all season. Afterward, though, he was practically ebullient.

“It was probably the most competitive match I’ve had,” Juan, 15, said. “It was fun; it was really fun.”

Juan and his identical twin, Antonio, are two of 20 Eagle Academy students who are avidly learning the game — and studying science, math and character lessons — with the Bridge Golf Foundation of Harlem. The group’s mission is to improve the lives and opportunities of young minority men through golf.

An instructor, Brian Hwang, drives at the Bridge club. Antonio Cortorreal, 15, is one of his students. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

The golf program is the latest in a growing number of organizations in New York and across the country devoted to introducing minority youths to sports traditionally played mostly by whites and to providing mentoring and tutoring programs. Harlem alone has StreetSquash; Ice Hockey in Harlem; Harlem Lacrosse; and Dream, formerly Harlem RBI, which focuses on baseball and softball.

At a time when Harlem is undergoing rapid change — to the disappointment and outright disgust of some longtime residents — Farrell Evans, the primary architect of the golf foundation, said the program represents a model for progressive gentrification.

“People get too caught up on the idea of displacement,” said Mr. Evans, who has lived in Harlem for 17 years. “We’re an example of how you can make it work for everybody.”

The foundation, located on West 117th Street between Fifth and Lenox Avenues, is part of a neighborhood that bears little resemblance to how it looked just a few years ago. A Whole Foods opened at 125th Street and Lenox Avenue in late July, a capstone to a boulevard of restored brownstones where bistros and upscale coffee shops now outnumber the remaining dollar stores and bodegas.

Whole Foods Market opened in Harlem in July. Its arrival is one of the changes that has longtime residents of the neighborhood concerned about gentrification. Image: CHANG W. LEE / THE NEW YORK TIMES

It’s not hard to find Harlem residents who lament the influx of wealth and newcomers in a neighborhood that once held the heart of black culture in America.

A community effort — backed by Adriano Espaillat, the Democrat who represents the 13th Congressional District — is afoot to thwart the real estate industry’s effort to rebrand the area between West 110th and West 125th Streets as SoHa (short for South Harlem).

Mr. Espaillat, who was unfamiliar with the Bridge Golf Foundation, said in an interview that any after-school program that provides academic enrichment, especially in science and technology, could be of great help to students anywhere. But he also said the foundation’s mission struck him as being “somewhat paternalistic” in what he considered to be an effort to “take students out of the basketball court and teach them a game where they can brush elbows with the very rich and elite of this city.”

“SoHa, Whole Foods, displacement,” he said. “Is success coming at the expense of people that are living there?”

“SoHa, Whole Foods, displacement,” he said. “Is success coming at the expense of people that are living there?”

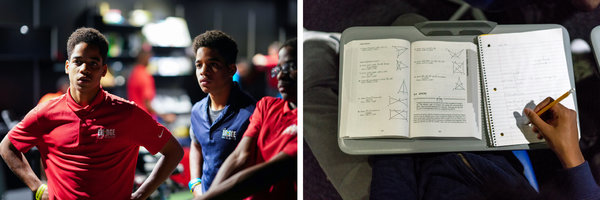

Antonio Cortorreal, left, and his twin brother, Juan, during a golf lesson; STEM subjects are part of the curriculum. Images: LEFT: CHANG W. LEE / THE NEW YORK TIMES RIGHT: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

The Bridge Golf Learning Center, also the headquarters for the foundation, opened in May 2016. The center occupies a street-level space in the rear of a luxury condominium called the Adeline that was built in 2014.

The facility has three hitting bays. Cups for putting are sunk into the carpeted floor. When the foundation isn’t in session with the students, the center is open to the public — generally a high-paying clientele — for lessons with golf pros, club fittings, fitness screenings and open play on state-of-the-art simulators that spew data such as club speed and carry distance.

Juan and Antonio know all of their numbers.

“Today I hit 275,” Juan said on a recent afternoon at the learning center, referring to how many yards he hit the ball off a tee with his driver. It was his longest drive yet. Antonio’s was 266. Either would be the envy of most recreational golfers.

The students at the center are seventh through 10th graders. All of them have enrolled by choice, but as a requirement of enrollment they must go to the learning center at least four days a week after school.

The organization also offers a seven-week summer program. Many of the students spent July and the first half of August preparing for state Regents exams. The twins focused on geometry, Juan in hopes of improving upon a 72, Antonio with the goal of passing. Each passed the earth science exam with ease.

Students must attend classes after school four days a week at the learning center. From left, Charlie Cohen, an instructor, works with Jacob Scarborough and Braylan Stewarts. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Sitting in their fourth-floor walk-up, above a West African grocery and a shuttered pizzeria, the twins’ father, Hector Cortorreal, said the golf center, along with Eagle Academy, the public school his sons attend, has provided much-needed focus in their lives. “I always see them doing their homework,” he said, gesturing toward the dining table in the narrow apartment.

The Eagle Academy for Young Men of Harlem is one of six schools — one in each New York City borough and another in Newark — run by the Eagle Academy Foundation. The Bridge Golf Foundation chose to become partners with Eagle Academy, Mr. Evans said, because their missions align. Each is dedicated to providing educational opportunities to urban young men of color. He said his foundation drew inspiration from the national movement to better address the needs of this at-risk group, citing former President Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative and the Young Men’s Initiative spearheaded by former Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg.

Both the Bridge Golf Foundation and the Eagle Academies include character education in their curriculums to encourage students’ social and emotional development. This summer, for example, the Bridge students read “The Pact,” a memoir about three young black men who, while growing up in Newark, promised one another they would become doctors and overcame hardships to fulfill their dream.

The Cortorreal family emigrated from the Dominican Republic when Juan and Antonio, the youngest of five siblings, were 7 years old. Their father is a porter in a building around the block. Their mother, Marisol, works as a home health attendant. The parents are no longer together, and the boys are living with their father.

As talented yet underprivileged young men, the Cortorreals are just the kind of the students the Bridge Golf Foundation was made for, Mr. Evans said.

Stretching before play at the Bridge. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Mr. Evans, a former journalist who grew up playing golf in a black middle-class family, started the foundation with Robert M. Rubin, a retired commodities trader who came from a white working-class background and is now the principal owner of the Bridge, a lavish country club in Bridgehampton. The two men met in the fall of 2014 while playing golf with a mutual friend in Westchester County.

As they strolled the fairways, Mr. Rubin and Mr. Evans shared stories of their backgrounds in the sport.

Mr. Evans, 42, grew up in Forsyth, Ga., a small town 60 miles south of Atlanta. He started playing as a youth with an old set of clubs of his father’s he found in the family barn. Although his dad no longer played, his extended family was deeply involved in the sport. His uncle, J. P. Evans, was a scratch, or expert, player who in the early 1970s helped desegregate the public course where his nephew would learn the game 15 years later.

In high school, Mr. Evans competed in predominantly black junior tournaments in Detroit, Cincinnati and Dayton, Ohio. In college, he played on the golf team at Florida A&M University.

When he met Mr. Rubin, Mr. Evans was writing about golf for ESPN.com. His connection to the golf industry began when he landed an internship with the PGA Tour as part of an effort to increase opportunities for minorities in the sport. The Tour began the program in response to the controversy surrounding the 1990 P.G.A. Championship, which had been held at Shoal Creek, then an all-white country club outside Birmingham, Ala.

Farrell Evans, left, a co-creator of the Bridge Golf Foundation, works with Juan Cortorreal, 15. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Mr. Rubin, 63, came to golf later in life. The son of an appliance repairman, he grew up in Monmouth County, N.J, with zero ties to the sport. After college, he went to work on Wall Street. Only then did he learn what currency golf has in the business world.

Mr. Rubin founded his club, the Bridge, in 2002. It self-consciously shirks tradition. The rolling grounds unfurl across the site of an old racetrack, relics of which, including flag stations and a spectator bridge advertising Chevron gasolines, still dot the property. The initiation fee is $975,000.

When Mr. Evans and Mr. Rubin strolled along the fairways of Westchester County that day, trading stories, Mr. Evans asked him, “Have you ever thought about doing something around golf with kids in the city?” Mr. Rubin was interested. Within a week, Mr. Evans had come up with a plan.

The two men established the nonprofit foundation in January 2015.

The annual budget is roughly $1 million, Mr. Evans said. Most of the funding comes from donations, with the major benefactor being Mr. Rubin. His motivation in underwriting the organization, he said, comes from what he considers a growing inequality of opportunity in America.

“I think there is a self-reinforcing, protectionist mechanism among the elites, and I’m thinking about ways to crack that,” Mr. Rubin explained. “The system that gave me my opportunity is broken now. So this is a way to create little openings in the armor that the elite have built around themselves.”

While President Trump, with his gilded private clubs, has become for many the face of golf in America, the foundation reflects a far different mission within the game.

Along the walls of the learning center are sculptures made from old leather golf bags by the conceptual artist Charles McGill, who was black (he died in July after a brief illness). The golf bag, he wrote in an exposition on prominent display, is “a very political object due to its historical associations with class inequality and racial injustice.”

Tariq Washington attempts to leave the sand trap at the Bridge. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Not only were many country clubs and municipal courses once segregated, so, too, were the ranks of professional golf. The Professional Golfers Association of America, the precursor of the PGA Tour, maintained a Caucasians-only policy until 1961, forcing pioneering black pros, including Ted Rhodes and Charlie Sifford, to play for years on African-American circuits. Sifford became the first black professional golfer to break the color barrier, but although he went on to win two PGA events, his best years were behind him.

It was in light of this history, and the ongoing plight of minority men in America today, that Mr. Evans came up with the idea of a youth golf program with an academic track in Harlem.

Early on, Mr. Evans recalled, people asked him why he was focusing exclusively on young, male minorities. “I said, ‘All you have to do is read the newspaper, look at your nightly news.’ It doesn’t take rocket science to see what’s going on in America.”

The Bridge students have examined issues of race through STEM as well as golf. Antonio was part of a team of students who researched the water contamination crisis in Flint, Mich. They presented their findings at a water-themed fair at the foundation in June.

The scandal’s disproportionate effect on Flint’s poor black population made an impression on Antonio. “It just seemed unfair to me that they had to drink that water,” he said.

The majority of the foundation’s STEM lessons are designed around the physics and statistics of golf. The students explore physics principles like the magnus effect, a lift force that determines the flight of a spinning ball. They also design their own experiments to determine, say, mean, mode and median and the correlation between two factors, like a golf club’s loft and the rotation of a ball.

Brian Hwang, right, works with Noah Folks at the Bridge. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

“You learn statistics in school and you think that it’s boring and why the hell are they making me do this?” said Veeshan Narinesingh, a co-leader of the Bridge’s STEM program. “But they see it in an actual application to something they care about and it sticks in their head more.”

The foundation began working with Eagle Academy students in September 2015. The learning center was still under construction, so the classes met at the Harlem Y.M.C.A. The boys swung plastic clubs until the center opened eight months later.

“As soon as we put a real club in their hands, they wanted to swing it,” said Brian Hwang, one of the foundation’s two full-time teaching pros. “And then they started to hit their first shots into the screens. That was it — they loved it.”

As the only boys’ high school golf team in Harlem, one composed entirely of freshmen, Eagle Academy lost every match last spring. Still, the boys said they gained valuable experience. The season produced highs as well as lows.

“Look at this shot!” Randy Taylor, the foundation’s other full-time pro, said during the Bronx Science match last spring as a drive of Antonio’s flew toward the green at Mosholu’s third hole, stopping 10 feet from the cup.

Mr. Taylor, 35, grew up in a family of modest means in Bridgeport, Conn., and took up the game at the insistence of his mother, who enrolled him in an after-school program that combined golf and academics. When he was 14, Mr. Taylor met Tiger Woods, then a rising star, who awarded him a scholarship to a Nike golf camp.

“I tell the boys all the time,” said Mr. Taylor, “that changed a lot for me and put me in a situation where I could learn this game of golf, be good at it and teach it for a living, and pass it on to them.”

Juan Cortorreal on the fairway at the Bridge. Image: JOHNNY MILANO FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

A few times a year, the foundation hosts the students at the Bridge, Mr. Rubin’s club.

Their most recent visit, in late July, combined hands-on lessons on how a golf course is maintained with sumptuous food, an instructional clinic and time spent playing on the course.

After a work session in the morning and a lunch of quesadillas, cheeseburgers and push-up pops on the club’s patio, the boys limbered up for golf lessons. Then they hiked to the first tee.

Zion Smith, 14, hit his opening drive and then took a moment to admire the verdant tableau, with its views of Peconic Bay in the distance. “It’s different than every other course I’ve played,” he said. “Everything is just so clean.”

Far more than just offering the occasional day in the country or an introduction to golf, Zion said, the foundation has become a second family to him after his father died of cancer.

“It’s very helpful to have people around to support me, that want me to be successful just like my father was,” he said. “They’re kind of stepping in as a parent figure in my father’s shoes, treating me special. Like I’m someone and not invisible, not being ignored.”

Article by: Paul Rogers - New York Times